I am going to Scotland for a few days. While I am away I thought I'd leave you with this long post. Apologies if it seems a bit self-indulgent ...

I have just finished reading Ann Leslie's excellent book Killing My Own Snakes ("the extraordinary life of a Fleet Street legend"). Leslie has been a foreign correspondent for the Daily Mail for over 40 years and the book offers a fascinating insight into that rather murky world.

One chapter brought back a lot of memories. Leslie describes how a year after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 she and her husband Michael went on holiday to Austria where they got a tourist visa to cross the border into western Czechoslovakia to visit some Slovak friends:

The worst moment for us came on departure. Our friends - and other Slovaks whom we'd never met before - asked us if we would smuggle out letters addressed to contacts in the West. What should we do if the border police searched us? One of our friends told us firmly, 'In that case, you must eat letters. Authorities must not read them!'

Between Bratislava and the Austrian border we stopped the car and, amateurish to a degree, decided to hide the letters under the carpets. At the border post we joined a lengthy queue of Austrian-registered cars. And to our horror saw that every one of them was being meticulously searched. 'My God, they're even removing the hub-caps,' I quivered to Michael. When the border police eventually reached us they made a thorough search of our luggage, removed the hub-caps, looked underneath the car but, eventually, waved us through.

Back in London, as I posted the letters, I felt a huge swell of anger about a political system which was so cruel, so utterly pointless.

Five years later, in 1974, Leslie joined a small tour group visiting Moscow and Leningrad (now St Petersburg):

Leonid Brezhnev was in power and the Soviet gerontocracy ... presided over a vast, decrepit, corrupt, shambolically incompetent and heavily armed empire covering eleven time zones - which, by then, was only being held together by the glue of fear.

Communist ideology as a quasi-religious faith had long ago died in the crushed citizenry's hearts (although it still showed signs of extremely vigorous life in the West among those who Lenin had called the 'useful idiots' of the Left).

In its Russian heartland it only existed in bombastic Party slogans on red banners plastered over public buildings: 'Let Us Make Moscow the Model Communist City!', 'Let Us Celebrate the Triumph of the Proletariat!, 'We Will Drive Mankind Forcibly Towards Happiness!'

Killing My Own Snakes by Ann Leslie, Macmillan, 2008

The same banners were still decorating public buildings and the Soviet Union was still held together by the "glue of fear" when I paid my own visit to Moscow in 1981, nine months after leaving university.

Time tends to dull the memory. However I discovered recently that my mother has kept some of the letters that I wrote when I was a student at Aberdeen and when I first moved to London after graduation.

One letter, written in April 1981 when I was 22, describes that trip to the USSR. At the time I was working for a PR company in London and I had told my parents that I was going to be "out of town on business". I was being economical with the truth. The letter, written a day or two after I returned, explains all:

Dear Mum and Dad,

First of all, I have a confession to make. I was indeed “out of town” last week but not, as I may have led you to believe, on business.

In actual fact I spent seven nights in Moscow. I travelled alone, although I was booked onto a Thomson package tour, and my job was to take various books and magazines into the country, give them to a contact, and then visit a second person who was to give me a letter which I was to bring out of the country.

Because there was an element of risk I decided not to let you know in advance. Not, obviously, because I thought you would react hysterically to the idea, but because it would have been natural for you to spend the week worrying. (Truth is, had I been caught they would probably only have deported me.)

Anyway, the story began in January when I was introduced to X, a Russian dissident living in London. Between then and leaving for Moscow I had around ten briefing sessions, each one lasting two hours, which covered such topics as cover story, how to detect if I was being followed, how to behave and what to do if caught etc etc.

In addition, I had to learn the addresses of my contacts, what they would look like, code words etc, none of which could be written down in case I was apprehended.

These meetings generally took place after work in the evenings, or occasionally on Sunday mornings. Sometimes we used Y’s flat in London but when that was not available X and I had to meet in coffee bars around Victoria Station, or in pubs. On one occasion we walked through Hyde Park discussing how I should pass the time if I was caught and put in jail!

I felt that this was a risk worth taking, if only because the opportunity may never come again. I must confess that my initial reaction, when asked to go, had been to think: “How nice, a free holiday in Russia!”. This attitude soon changed however and having met my contacts in Moscow I can’t tell you how exhilarating it was, knowing that I was helping them in some small way. But more of that later.

All the literature I was taking was printed in Russian. It was largely about Poland and Afghanistan. When I saw the amount I had to carry I was slightly dubious, particularly as I had to carry it on my body and not in my baggage which would almost certainly be checked at [Moscow] airport.

I should mention that the Helsinki Agreement allows for this sort of literature to pass from one country to another, but the Soviets won’t accept this. So the material, consisting of 12 books the size of a pocket diary, various magazines and leaflets, had to be sown into place - on my chest and under my arms - between two t-shirts. I then had to pull on a thick woollen jumper, a jacket and an overcoat which made me look like Billy Bunter! In addition I had a letter, typed on silk, sown into the sleeve of my jacket.

One problem, though: because all airport authorities sometimes do body searches, I couldn’t afford to be delayed at Gatwick trying to explain why I had Russian-language books and magazines stitched into my clothes, so I had to take everything on to the plane in my hand luggage. [Note: in those days outgoing hand luggage was rarely searched at UK airports.]

Once in the air I had to go to the loo where I struggled to put the t-shirts on under my rugby shirt, with my woollen jumper and jacket on top. As you can imagine, it got extremely hot!

We arrived in Moscow at 7.50pm and so to the most nerve-wracking bit of the whole trip. Several people had their luggage checked for books (which showed up on the x-ray machines) but all they found were novels or tourist guides. Worryingly, the person directly in front of me was body searched so the old heart began to pump a bit! Luckily it was all a bit random and I managed to get through without being searched at all – huge relief!

The hotel where I stayed was described as “small” by our Soviet guides: in fact it had 20 floors, six bars and three restaurants and was 400 yards from Red Square and the Kremlin.

We arrived at the hotel at 11.00pm and after checking in I walked the short distance to Red Square. It was incredibly quiet. The roads were empty and it was unbelievably cold. I have never felt so far from home!

I was due to drop off the material at the first address before breakfast on Sunday (our first full day in Moscow) but I slept in and had to go on a pre-arranged tour of the Kremlin instead. It would have looked suspicious had I missed it.

Of course, I had to keep the books and magazines on me at all times in case our hotel rooms were searched. In fact one of the first things I had to do when I checked in was to take off the t-shirts and put the books etc in a Russian-style shoulder-bag. Unfortunately no-one had told me that bags were not allowed inside the Kremlin so I had a slightly worrying two hours while my bag - with all the books and magazines - sat on my seat in the coach completely unattended.

When, finally, I reached the block where my first contact lives, I found there was a door inside the entrance that I hadn't been told about. Needless to say it was locked. My contact lived on the sixth floor so there was nothing I could do to gain entry.

As a result I had to go back the next day, before breakfast. This time the door was open so I was able to climb the stairs to the sixth floor. I knocked on the door and a man opened it. I gave the password, he nodded. I handed over all the books and magazines. And that was it.

After dinner, following a tour of the city and a visit to the Exhibition of Economic Achievements, I set off for the second address. This was much further away and it was dark and very cold. I had some difficulty finding it because the directions I had been given were not very accurate. Eventually I found it but I was a long way from the usual tourist areas and I felt very conspicuous.

The man I was supposed to meet was out at work, even though it was 9.00pm. So I arranged with his wife to return at four o'clock the next day ...

The following day I returned to their apartment and spent over two hours with the pair of them. I cut the letter from the sleeve of my jacket and his wife sewed a fresh letter into the sleeve for me to bring back to London.

Z hardly spoke any English at all, although he could understand a fair bit, but his wife had studied English at university. She rarely gets the chance to practise and frequently had to look at her dictionary, which caused a lot of amusement. She was the same age as me. Z was nearer 30 and was very thin with a thickish beard.

We talked about all sorts of things and had a good laugh. I was very pleased when they asked me to come back later in the week. However I had been told that it was not a good idea to return to an address more than once, but Z and his wife didn’t think the risk was too great so I agreed to visit them again.

Throughout my stay I never felt worried about my own safety (apart from that brief period at Moscow airport) but I felt a lot of responsibility for my contacts. Z and his wife were so charming. Z’s mother lived with them but they were anxious that she wasn't implicated in anything so we were never introduced. When I asked them why they took such risks they were slightly embarrassed and said that if I lived in Moscow I would understand.

In fact a week in Moscow was more than enough to develop an impression of the place. Frankly, it’s a hell-hole. Apart from Red Square and the Kremlin, it’s grey and bleak – quite horrible. Everything seems to be in decay – paint and plaster falling off the walls, rubble everywhere. People queue outside shops, the liquor stores are full (vodka was always sold out by lunchtime) and the food is terrible – and never varies. Shortages are the norm.

My second visit to Z and his wife was on Saturday morning, prior to my flight home. Again I stayed for two hours before returning to the hotel. I had suggested that Z write a second letter for me to take to London, and this had to be sewn into my other sleeve!

There are many more things to tell you about my visit – for example, I saw the Moscow State Circus and visited Lenin’s Mausoleum. In the meantime, hope you understand why I decided not to tell you in advance …

I was one of hundreds, probably thousands, of “couriers” who "smuggled" literature in and out of the Soviet Union. Several were friends from university. One was detained (at Moscow Airport) and deported within 24 hours. Another was arrested in Red Square handing out Russian language leaflets he had smuggled into the country. He too was deported.

As for Lenin's "useful idiots", many of them are still with us, in the Labour party and elsewhere. Truth is, some wars never end.

Monday, August 31, 2009

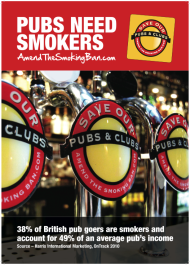

Monday, August 31, 2009  I understand that the "Smoking' Festival" at the Jolly Brewer in Lincoln (see previous post HERE) was a great success. Pat Nurse, who lives locally, has sent me a photo of "legendary local guitarist Jon Gomm" wearing a Save Our Pubs and Clubs t-shirt.

I understand that the "Smoking' Festival" at the Jolly Brewer in Lincoln (see previous post HERE) was a great success. Pat Nurse, who lives locally, has sent me a photo of "legendary local guitarist Jon Gomm" wearing a Save Our Pubs and Clubs t-shirt.